WAR TOYS – 2014

One man exhibition. Pangolin London Gallery, Kings Place, London

In the August 2014 issue of “Galleries” the critic Nicholas Usherwood wrote:

“Entitled ‘War Toys’, Steve Hurst’s exhibition at Pangolin London may prove to be one of the more profoundly satirical shows relating to the First World War to be seen in London this year. A child through the course of World War Two and with 10 years in National Service and Territorial/reserve positions, Hurst knows what he is talking about. This group of small sculptures and artefacts comes out of a residency at the In Flanders Fields Museum at Ypres and the discovery of the curious Battlefield Cafe Museums with their weird mixture of mud and rust-covered relics and coloured tourist kitch objects. It also raised resonances of war-toys and man’s ambivalent fascination with them. Fierce, witty and curiously touching, this is a show that reverberates.”

There is a connection with Stephen’s ‘Early Works’

Her drawing has a freedom of line, a concept of space, and attention to detail. To put it simply, she has that total control and total confidence that is at the service of an imagination that appears almost limitless. No doubt it was that same force that compelled the primitive humans that decorated the Lascaux caves to take up soot from the embers and ochre from the earth and start drawing.

What is this force? It does not matter. All that matters is that the artist accepts that it exists. It is there and all he has to do is to tap into it.

Rosie lives for most of the year in the far North East of China, in Laoning Province. She knows nothing of galleries, or critics, or applying for funds to the Arts Council, or grovelling to a patron. She is that rare being a genuinely free spirit. So it seems that it is these intrusive forces that kill that primeval lust to make art. There is an affinity between the very young and the old. The one has not yet encountered those negative forces, superficially dedicated to ‘Art’ that retard, bribe, seduce and finally kill that primitive instinct to make real art. The other is a survivor who has run the gauntlet, the trial by fire. If he survives and continues, obstinately, to make art then he has put himself outside the system. He has discarded all petty ambition and simply wants to be left alone to get on with this thing that has obsessed and eluded him all his life.

During the aftermath of the Second World War the Paris based painter, Jean Dubuffet, wrote of the false and the real Mr Art. The former he described as a “Laurelled understudy” who is “led through the streets by the conference people with a ring through his nose”. The real Mr Art, Dubuffet said “Goes ever incognito. He is most at home where no one knows him, where they do not even know his name.”

Picasso, amongst others, described childhood as a vast store-house of memory and visual impressions. He wrote: “It took me forty years to learn to paint like Raphael, rather longer to learn to paint like a child”

My childhood was lived in a time of war and my student period through the Cold War which was also a period of many small Colonial wars. Thus through childhood adolescence and young manhood I knew nothing but wars and preparation for war.

Historians and politicians gloss over the waste of human life. They overlook another major factor – the prodigious waste of precious materials. If we take a battle at random, such as the Battle of Britain 1940-1941, which small boys watched in fascination, expensive and marvellously made pieces of machinery fell out of the blue. We picked them up, or looted the carcasses of aircraft that came screaming and smoking out of the sky. My happiest time, during an unhappy and boring schooling, was spent gleaning the countryside for fallen or discarded war machinery. My Father was away in Egypt throughout the war but he left me in charge of his workshop and there I hoarded intricate pieces of steel, brass, copper, bronze and above all aluminium. I developed a love of scrap metal that has never left me. Then there was wood. I made things out of metal as a child but far more often used wood because it was easier to work. Through two world wars, every piece of machinery, equipment, tool, or weapon was housed, protected and transported in a wooden box. Most numerous of all were ammunition boxes, millions and millions of rounds of ammunition from rifle cartridges to howitzer shells. Hundreds of small backstreet factories turned out tens of thousands of these boxes. In the war’s aftermath these became available either simply dumped in pits or ponds or sold through a mass of war-surplus shops.

Finally there was top quality plywood. This was used in a glued together or laminated to form a variety of aircraft from gliders to the De Haviland Mosquito. When he returned from the Middle East my Dad bought two large trailer loads of dismembered glider plywood. This was not only a rich hoard of material but of colour. The extraordinary selection of colours ranging from camouflage to the bright yellow of the Epoxy Resin that held parts of the glider together to rich red browns and grey greens of the interior paint.

The BBC commentator, Katherine Whitehorn, spoke of her childhood in a series of programmes known as My Generation. She spoke of the extraordinary and never-to-be-repeated freedom gained by herself and all of her generation during the war. We ran wild in feral packs. For me and my fellow gang members our playground was the Thames valley. The war-photographer Don McCullin describes a similar gang of undisciplined children playing in the bombed ruins of East London. As Whitehorn remarked there was a freedom unknown to children today. A common admonition by our elders was “Don’t you know there’s a war on?” Yes there was a war on and we were well aware of it. Death was a close companion. My wife is the only person of my generation who I know well who was, as a very young child, physically blown through the air by an explosion. This happened to be a Flying Bomb (or V One ). This violent experience appears to have had very little impression on her. On the other hand her Sister, who is several years older, has remained nervous and easily frightened.

(Much later, when I went to teach in Belfast during the ‘Troubles, I met several men and women who had been blown up. They were the lucky ones. Like Sylvie they survived).

In time of war children become very observant, they notice everything that goes on around them. If the child is encouraged to draw and to make things then those art works will reflect what he observes. In a time of war children make war-toys. We call them toys but they are far more important than mere playthings. If you explore an ethnographical museum (the Pitt Rivers in Oxford is a good example) you begin to discover the importance of toys throughout human history. When does a toy become a religious Ikon? When does a toy become a fetish or a weapon of war?

2011-2012

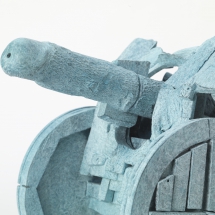

Bronze

Edition of 6

56 cm wide

2012

Bronze

Edition of 6

62 cm wide

2011-2012

Working model

Painted Wood, Unique

82 cm wide

2011-2012

Working model

Painted Wood, Unique

51 cm wide

2012

Bronze

Edition of 6

52 cm high

2003

Painted wood

Unique

68 cm high

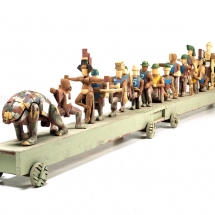

2005, Painted wood

Unique

350 cm wide