THE SOMME

The sixtieth anniversary of the First Day on the Somme (July 1966) both enraged and inspired a number of young writers and artists. These included Pat Barker who created her trilogy based on the history of the Great War.

Chance took me to the country lane that connected the villages of Auchonvilliers and Beaumont-Hamel. I came on two cemeteries that contained the remains of the majority of one battalion of London volunteers. This led me to a search for the truth about this massacre and the search, in turn, had results in both written and sculptural form.

My primary aim in walking or cycling this one section of the Somme battlefield throughout the nineteen seventies was an attempt to discover what happened to one volunteer Battalion, the 16th Middlesex, and why so many of the Battalion died in this small area of ground. I could not fail to affected by the landscape and the marks made upon it either by digging or the constant barrage of high explosive designed to disrupt or kill the diggers. 40 years ago much remained that has since been cleared away or buried by new and more powerful earth-moving machinery. For example, most of the smaller mine craters and larger shell holes have been filled in. Back then these were a very noticeable feature of the landscape as was the quantity of thick barbed wire pushed into thickets or holes in the ground and, not least, the quantity of metal objects still on the surface of fields or abandoned in woods and coppices. The resilience and protective quality of the chalk was obvious and this was a key element in the German defence. Like the uncut wire the density of the chalk was ignored by British Army Intelligence branch of Haig’s Staff. The chalk is so uniform in texture that many soldiers carved souvenirs out of it.

I became familiar with this one section of the old front line through many short visits over a decade. I combined visual and tactile research with interviews with a small number of survivors who I met through our Regimental Association. Both, very different, types of research made a deep impression on me. Emotion combined admiration for the men I knew with grief and anger at the callous stupidity of both the military and the civil establishment. The result was twofold – a book (that took thirty years to find a publisher) and a series of coloured reliefs made of plywood and aluminium and painted with oil paint. Finally I started to make objects.

Drawing the landscape, experiencing all it’s moods, sunny or windswept or wet, combined with the objects that I found, transformed my sculpture. (I was teaching at Chelsea School of Art at the time and many of my colleagues believed it changed for the worse). I abandoned abstract, minimal sculpture, which was the vogue in the galleries and in the art schools at the time, and I went all out in an attempt to express the deep, often painful emotions that I felt about war in the 20th Century. This included not only the Great War, which ended 14 years before I was born, but the Second World War that I experienced as a child.

THE SOMME: SERIES ONE

The first works were a series of drawings made over three days on the site of the Front Line at Beaumont Hamel. These resulted in a number of reliefs made of plywood and painted. Aluminium parts were either war debris or castings made in the foundry at Chelsea School of Art. The two sculptures “Wayland” and ‘Y Ravine’ were also made while I was teaching at Chelsea.

The influence of the waste of life of the Somme Battle (1916-1917) extended to two series. The first consisted of painted reliefs and the second cast in bronze.

SERIES TWO: LUXEMBOURG

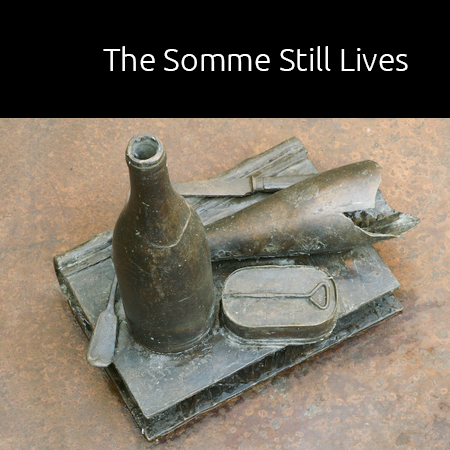

The second Somme series came ten years later. They are all still-lives inspired by a shallow excavation made near the Lochnagar mine crater at La Boisselle. Removing the top-soil revealed the detritus of daily trench life. The trench happened to be the German Front Line but I wanted to make the still-lives representative of ordinary soldiers of every nationality.

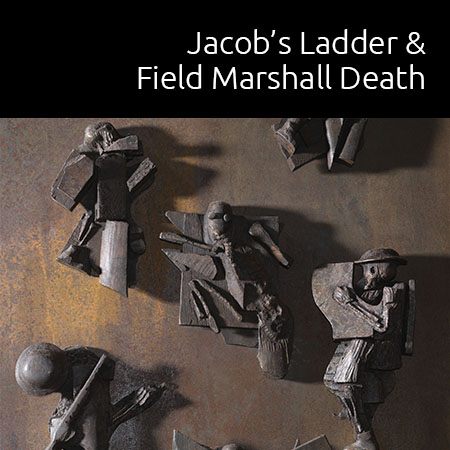

JACOB’S LADDER AND FIELD MARSHALL DEATH

There is a difference in time of completion, (Jacobs Ladder – 2013 and Field Marshal Death – 2016) but the two are related. They are made of the same materials – steel, cast-iron and bronze. More important, each sculpture refers back to the period when I researched a section of the Northern end of the Somme battlefield, the cliffs along the Ancre Valley from Aveluy Wood to Beaumont Hamel. The research took place over several summer blocks, spread over the years 1968 to the mid nineteen seventies. The aim was observing, surveying and getting to know the ground by drawing and crude mapping as well as making written notes. Spending so much time in one place I could see where the nature of the tragedy lay, in the superior use of the defenders of both the ground and underground (the solid and largely shell-proof nature of the chalk)